The Good: Mining Their Own Business

The Trump administration has begun acting on its campaign promises to expand domestic manufacturing and reduce reliance on key trade partners. A major focus has been securing critical mineral supplies, with ongoing negotiations involving Ukraine and Russia for potential agreements on rare earth minerals and other essential resources. These efforts aim to strengthen US supply chains and reduce dependence on foreign resources in strategically vital sectors.

Rare earths, a group of 17 chemically related elements, are critical to the production of electronic devices, defence technologies, and renewable energy solutions. While they are not geologically scarce, their concentrations are typically too low to justify the costly and environmentally intensive extraction process. Mining rare earths requires extensive infrastructure, significant capital investment, and years of development before becoming economically viable. Furthermore, processing these minerals involves chemically intensive methods that generate toxic waste, leading to strict environmental regulations that further complicate domestic production.

America’s push to establish a competitive rare earth supply chain faces major obstacles. China’s strategic control has driven down prices, making new projects financially unsustainable, while geopolitical tensions add further complexity. Although China produces roughly 70% of the world’s rare earths, it dominates refining and permanent magnet manufacturing—controlling over 90% of capacity—giving it outsized influence over global supply and demand. Reducing reliance on China will require not only significant investment but also long-term strategic planning and international cooperation from Western allies.

Despite these challenges, some clear beneficiaries have emerged in the near term. One such winner is MP Materials, a holding within the High Street Wealth Warriors Fund. The company owns and operates Mountain Pass, the only fully integrated rare earth mining and processing site in North America. MP Materials recently reported strong earnings, with a 47% increase in revenue driven by commercial production of NdPr metals and progress toward full-scale production of automotive-grade magnets. Strategic initiatives, including supply agreements with major automakers and the Department of Defense, as well as a significant tax credit for its Independence facility, highlight progress towards strengthening the US rare earth supply chain.

The Bad: A Taxing Trade-Off

On February 19th, South Africans were eagerly awaiting the delivery of the first annual budget under the new Government of National Unity (GNU). However, after strong backlash from coalition partners, Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana was forced to postpone the unveiling of the national budget – the first delay of its kind in post-apartheid South Africa.

This is the first time in the democratic era that the African National Congress (ANC) needed the support of other parties to pass the budget. The Democratic Alliance (DA), the GNU’s second largest partner, had a major disagreement with the ANC’s proposal to raise value-added tax (VAT) by 2 percentage points. The ANC argued that VAT needs to be raised to plug holes in the education budget and support social spending, whereas the DA believes that the increase would have “broken the back of our economy.” VAT is a regressive tax, which means it disproportionately affects poorer people more compared to the wealthy. Raising VAT in one of the most unequal countries in terms of income distribution would lead to several negative outcomes.

The economy is forecast to grow at 1.8% per year from 2025 – 2027, while the interest that the country pays to its lenders is likely to represent almost 22% of government revenue in 2025 and is forecasted to rise by 6.9% per year from 2025 to 2028 according to the South African National Treasury.

An alternate solution is for the government to cut fiscal spending. The Treasury and the Finance Minister have committed to conducting a spending review, though no specific date has been set. However, given the delayed budget and past years’ trends, it’s clear that controlling expenditure has not been a key priority. To balance the budget without harming the poorest decile, many economists believe that the government must reduce fiscal spending. Deciding which of the expenses to be reduced has been discussed ad nauseum, but political commentators seem to agree on one thing: raising the VAT rate is not the answer.

Though the postponement was unexpected, the resistance from the GNU partners is a positive for all South Africans. Without it, the VAT rate could have been raised without opposition, along with other changes that a single-party majority government could have implemented without resistance.

& Not All Rand-Hedges Are Equal

In most cases, Rand-hedges refer to JSE-listed companies that generate most of their revenue in foreign currencies, such as the US dollar. As a result, these companies tend to benefit from a weakening Rand, effectively providing a ‘hedge’ against Rand depreciation.

There are two board categories of Rand-hedge shares:

(1) Dual-listed companies that are registered and operate aboard but are also listed on the JSE. Examples include Richemont and British American Tobacco.

(2) South African exporting companies (including most of the mining companies) whose revenues are set in hard currencies. Examples include Sasol and Anglo-American Platinum.

A key distinction between these two categories is where they operate. South African exporting companies have substantial operations within the country, making them vulnerable to local economic and political risks. This has been a major challenge for many of these businesses, as ongoing power and infrastructure issues have disrupted supply chains—from production all the way to getting their exports to port.

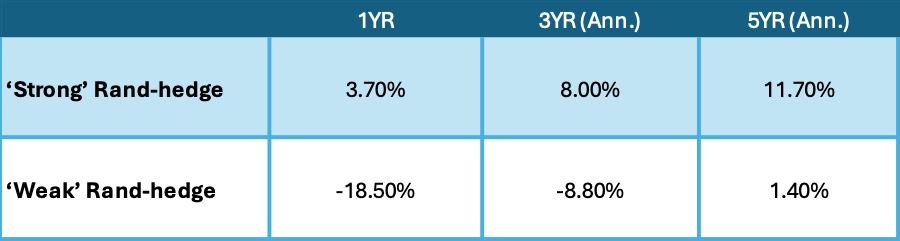

At High Street, we refine the Rand-hedge classification into what we call ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ Rand-hedges. ‘Strong’ Rand-hedges are companies that not only earn most of their revenue in foreign currencies but also have limited exposure to the South African operating environment. Specifically, these companies must have less than 30% of their operations or assets in South Africa. ‘Weak’ Rand-hedges, on the other hand, are companies with significant local operations, making them more susceptible to domestic risks. The table below outlines the performance of ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ Rand-hedges within the JSE Top 40 to the end of 2024:

Source: High Street Asset Management via Bloomberg. Data as of 31/12/2024

Although both groups generate revenue in foreign currencies, their performance has diverged significantly, largely due to the difference in exposure to South Africa’s operating risks. A clear example is Sasol. Historically, its share price closely followed the US dollar oil price. However, this correlation has broken down in recent years, with operational challenges in South Africa weighing heavily on the stock. Since the start of 2020, Sasol’s share price has declined by 73%, despite oil prices rising slightly.

In the High Street Balanced Prescient Fund (our Local Balanced Fund) we invest exclusively in ‘strong’ Rand-hedge companies within the local allocation. This aligns with our strategy of maximising offshore exposure and minimising South Africa-specific risks. The High Street Balanced Prescient Fund maintains 90%+ Rand-hedge exposure.